British spying: tentacles reach across Africa’s heads of states and business leaders

British spying: tentacles reach across Africa’s heads of states and business leaders

Par Simon Piel, Joan Tilouine

Dozens of politicians, diplomats, military and intelligence chiefs, members of the opposition and leading business figures were wiretapped across the continent.

This rare overview of modern satellite espionage could hardly be less technical and abstract, for it not only names the victims of intercepts but also reveals the scale of a surveillance operation spanning an entire continent. That continent is Africa. New documents shown to Le Monde, in collaboration with The Intercept, from the data cache of the former NSA (National Security Agency) operative Edward Snowden, originally given to Glenn Greenwald and Laura Poitras, offer unprecedented insight into information on twenty African countries collected by GCHQ, the British intelligence service, between 2009 and 2010.

Dozens of lists of intercepts examined by Le Monde journalists stem from a specific period of operations by GCHQ technicians. These reports celebrate GCHQ’s success in redirecting flows of satellite communications, and conclude that the agency could now proceed with systematic data collection.

The lists of hundreds of intercepts by GCHQ contain the names of heads of states, incumbent or former prime ministers, diplomats, military and intelligence chiefs, members of the opposition and leading figures from the world of business and the financial industry. These actions violated the political, economic and strategic sovereignty of twenty African countries, many of whose leaders were allies of Great Britain.

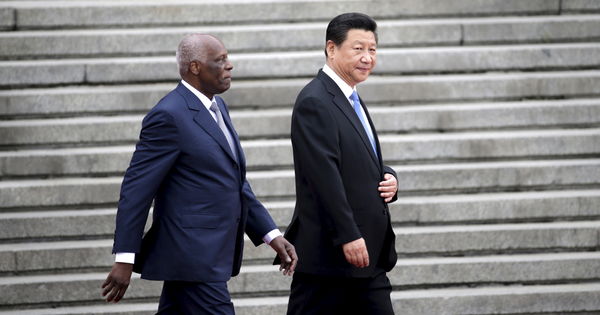

Heads of state and prime ministers

GCHQ’s main targets were heads of state and prime ministers. Although the UK was Kenya’s main trade partner, in March 2009 the British secret services intercepted communications by President Mwai Kibaki and his closest strategic advisers, as well as eavesdropping on Prime Minister Raila Odinga. They followed the same approach in Angola, Africa’s largest oil producer, which has been governed by President José Eduardo Dos Santos since 1979. The intercept reports show that Luanda’s presidential palace was under surveillance. At the time of the intercepts, Angola was suffering from a crash in commodity prices, and U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton visited Luanda to boost strategic cooperation between the two countries. Great Britain provided information to the United States to ensure the latter retained its stranglehold on the region.

Democratic Republic of the Congo's President Joseph Kabila inspecting a guard of honour during the celebrations of Congo’s independence in Kindu, June 30, 2016. He has been wiretaped by the British intelligence service | KENNY KATOMBE / REUTERS

Five hundred and seventy-four miles to the north, on the other side of the border that Angolan troops crossed to support Laurent Désiré Kabila during the Second Congo War (1998-2001), Kinshasa was also under close surveillance. Following his father’s assassination in January 2001, Kabila’s son Joseph took the reins of this gigantic African state, and British spies must have been intrigued by his activities, for they eavesdropped on all his communications and those of his close political, diplomatic and military advisers.

GCHQ also conducted massive intercepts in Nigeria, a former British colony and member of the Commonwealth. British agents listened in on phone calls by President Umaru Yar’Adua, his aide-de-camp and his main advisers, including his principal private secretary and his special adviser. GCHQ also targeted the vice-president of the continent’s most populous country and the largest economic power in the region. As the Nigerian head of state was already sick (he died on 5 May 2010), his successor Goodluck Jonathan’s phone line was also on the list of planned intercepts.

The same system was also in place for Ghana, where President John Kufuor and his colleagues were wiretapped, and in Sierra Leone, where calls to and from leader Ernest Koroma’s mobile number were intercepted. Further north, in Guinea-Conakry, the British were also eavesdropping on telephone and electronic communications made by Kabiné Komara, the prime minister of the junta led by President Moussa Dadis Camara, who had seized power in a putsch. Camara’s close advisers are also mentioned in the database to which Le Monde has been granted access. The telecommunications of the Togolese head of state Faure Gnassignbé were also intercepted.

Former presidents and prime ministers

The intercept lists from 2009 seen by Le Monde also feature several former heads of state and prime ministers whom the British and their allies appear to have continued to follow closely. The names include the former Nigerian president Olusegun Obasanjo (1999-2007) and his counterpart in Sierra Leone, Ahmed Tejan Kabbah (1998-2007). In this West African nation devastated by a decade-long civil war, one person attracted particular attention – the former president and warlord Charles Taylor, along with his principal lieutenants, some of whom controlled mercenary camps in the north of the country along the border with Guinea. GCHQ’s targets in the Guinean capital Conakry were Cellou Dalein Diallo and Lansana Kouyaté, both former prime ministers under the dictator Lansana Conté and now leading opposition figures.

The British were monitoring events in the eastern Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and in the presidential palace in Kinshasa, but in 2009 their surveillance of the other side of the river Congo was concentrated on the Republic of the Congo’s former head of state, Pascal Lissouba (1992-97), who lives in exile in France. Considered too close to U.S. and British oil companies, he was forced from power by Denis Sassou-Nguesso with French and Angolan backing.

Diplomats

GCHQ was also very interested in diplomats from these African countries. One of their targets, the Burkinabé Djibril Bassolé, told Le Monde: « What I said on the telephone was said in public ». He is currently in prison in Ouagadougou for « undermining state security » during the attempted coup in September 2015. Six year earlier, however, he had been Burkina Faso’s minister of foreign affairs, and he coordinated support for the rebellion in Côte d’Ivoire on behalf of President Blaise Compaoré. He was the Joint African Union-United Nations Chief Mediator during the Darfur crisis, and it was presumably his diplomatic activities that led the British secret services to put him on their list.

Surveillance of African diplomatic services was as widespread as the operations targeting their leaders. The British intelligence services eavesdropped on communications involving the foreign ministers of Nigeria, Kenya, Zimbabwe, Sudan and Libya, and their closest collaborators. Their emails were also intercepted. This allowed GCHQ to keep an eye on developments within these states and even monitor such delicate matters as the liberation of Western hostages, including a British man, held by Movement for the Emancipation of the Niger Delta (MEND), the Nigerian rebel group that ruled the swamps and waters of the Niger Delta. The British showed a keen interest in the offices of the Nigerian minister of foreign affairs, Ojo Maduekwe, and in particular his private landline and mobile numbers.

The British secret services also widened their espionage operations to African embassies, keeping a close watch on the Zimbabwean ambassador in Kinshasa, his DRC counterpart in Brasilia, the Sudanese embassy in Islamabad and the Nigerian embassies in Ankara, Pretoria, Tripoli, Yaoundé and Tehran, as well as Nigeria’s Permanent Mission to the United Nations in Geneva. In the Saudi Arabian capital, Riyadh, GCHQ targeted the embassies of Eritrea, Algeria, Guinea and Sudan. The Syrian ambassador to Khartoum also appears in the database, as do the Russian embassies in Conakry and Abuja. Close attention is paid to Chad’s diplomatic networks in the arc from Moscow to Tripoli.

Intelligence services and rebels

The British are equally interested in the intelligence services in these volatile African countries and in any rebel movements with the potential to replace the current rulers. GCHQ intercepted rebel movements’ telecommunications in Darfur in western Sudan after armed conflict broke out in 2003. Telephone lines used by various rebel leaders to call the United Arab Emirates, Qatar, Chad and Libya crop up in the data. One of them belonged to Jibril Ibrahim Mohammed, the brother of Khalil Ibrahim, the leader of the Justice and Equality Movement, who was killed in 2011. In a region plagued by rebellions, the British secret services followed telecommunications involving bosses of armed Sudanese and Chadian groups, as can be seen from intercepts targeting Albissaty Saleh Allazam of the Revolutionary Action Committee. Libya’s domestic and foreign intelligence services were a favourite target of their British counterparts. The same was true of DRC, where GCHQ kept the heads of the army and the security services under surveillance. Several intercepts are marked « Related to the Egyptian intelligence services ».

Several members of MEND, a militant group active in the oil-rich south of Nigeria, were wiretapped, as their attacks on tankers and pipelines posed a threat to the interests of British and American oil companies. MEND was holding a British hostage, and the British secret service listened in on this African powerhouse’s military and intelligence services, the Nigerian and British negotiators, and MEND’s leaders and members.

Bankers and businessmen

Yet GCHQ did not focus exclusively on politicians. The lists also feature some of the continents’ leading businessmen and bankers including the Kenyan Chris Kirubi. The Nigerian billionaire Tony Elumelu, regarded as one of Africa’s richest and most influential men, was also targeted by British agents in 2009. A friend of Nigeria’s then president Umaru Yar’Adua, Elumelu was at the helm of the United Bank for Africa (UBA).

The data includes the contact details of the Nigerian ministers of finance and oil, as well as those of various telecommunications operators and of major banks such as Zenith Bank. There are also details about the immensely wealthy Dahiru Mangal, the region’s smuggling kingpin, who hails from Katsina like the Nigerian president, and provides financial backing to his own president and to the head of state of Niger. In Lagos, Nigeria’s economic capital, the British made sure that they listened in on the telecommunications of the Africa Finance Corporation, a pan-African financial institution that funds infrastructure investment. Its vice-president Solomon Asamoah came in for particularly heavy surveillance.

In the Democratic Republic of Congo, GCHQ’s antennae were trained on the deputy minister for mines and Joseph Kabila’s all-powerful special adviser Augustin Katumba Mwanke. This discreet operator had complete control over mining contracts, and organised what the international community described as « the plundering of natural resources » for the ruling clan.

Other businessmen close to Joseph Kabila, including Victor Ngezayo, the head of a hotel group, were also under surveillance. Politics and business go hand in glove in Katanga, where the popular governor Moïse Katumbi has used his position to influence and profit from mining activities. A close ally of Joseph Kabila, who helped him amass his fortune, Mr Katumbi has rallied Kabila’s opponents with the aim of taking on his former master at the ballot box.

GCHQ also listened in on the telecommunications of foreign transnational corporations operating in Africa, one of their targets being Mediterranean Shipping Company, an Italian-Swiss logistics firm. Most telecommunications firms, including the South African company MTN, Saudi Telecom, France Télécom and Orange, were under surveillance.

Snowden files: our revelations

Le Monde worked directly, during several days, in collaboration with The Intercept, on the Edward Snowden archive given to Glenn Greenwald and Laura Poitras: tens of thousands of documents exfiltrated by the former agent from the NSA servers, and safely stored by The Intercept.

Those documents show :

- British spying: tentacles reach across Africa’s heads of stattes and business leaders

- British spies closely track mineral-rich Congo’s business dealings

- Britain spied on companies, diplomats and politicians in French-speaking Africa

How the GCHQ carefully monitored technology specialists working for Internet and phone service providers, mainly in Africa.

- How British intelligence targeted Octave Klaba, founder of the largest European web hosting company OVH.

This list will be updated with each new publication.